From Air Pollution To Waste, Has Hong Kong’s Environmental Report Card Improved Since 1997?

05 Jul 2022

05 Jul 2022

- Category

- Keywords

(5 July 2022 SCMP)

As Hong Kong has just celebrated the 25th anniversary of its return to China, it is worth reviewing some key environmental performance indicators to see if there has been improvement since 1997. The results would help Hong Kong’s new chief executive, John Lee Ka-chiu, set key performance indicators, which he has vowed to do and which are critical for Hong Kong’s sustainable development.

I recall a famous term from the pre-1997 era: “positive non-interventionism”. This was a guiding principle for the colonial government, which believed that a free market would drive success. This notion is correct to some extent, but when it comes to environmental or social issues, the government should not stand on the sidelines.

The United Nations identifies three core elements of sustainable development: economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection. Leaving out the environmental and social, while allowing market forces to hold full sway, has resulted in negative outcomes like pollution and financial hardship.

The Green Earth has reviewed seven key environment-related metrics from 1997 and 2020. While our city has seen improvements in three areas – noise, air pollution and water quality – it has scored badly in others such as waste management and nature conservation.

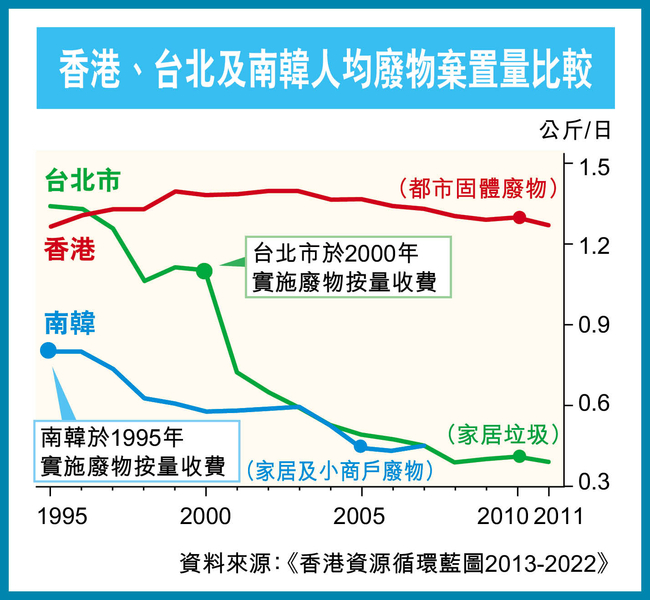

First, waste management: the amount of waste generated daily per capita in 1997 was 1.98kg. After almost a quarter of a century, this number showed no signs of dropping, but instead had climbed to 2.01kg in 2020. Over the past two decades, various waste management plans and policies have been launched by every administration, starting boldly with the first chief executive Tung Chee-hwa.

A major policy among many from the Waste Reduction Framework Plan launched in 1998 was the Landfill Charging Scheme. The aim was to introduce relevant legislation in 2000 to charge for the disposal of all types of waste except household waste.

It was a bold idea for its time. Interestingly, the environmental minister at the time, Bowen Leung Po-wing – then holding the title of Secretary for Planning, Environment and Lands – had successfully transitioned to the new Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government from the colonial administration.

However, had the responsible principal officials actually acted responsibly, it would not have taken more than two decades spanning five terms to get the municipal waste charging regulation – which expands on the original scheme to include household waste – approved by the Legislative Council. This was finally done in 2021, but we still need to wait until the second half of 2023 at the earliest for the legislation to come into effect.

The Lee administration must treat this ridiculously long delay as a valuable lesson and overhaul such an inefficient work culture.

Next, let’s look at nature conservation. The Chinese white dolphin was the mascot for Hong Kong’s handover in 1997, supposedly bringing good luck to the city. At the time, around 250 white dolphins were counted in Hong Kong waters.

Yet despite some protection measures by the government, the number of white dolphins has kept dropping and only 37 were found in 2021. There are fears that any further large-scale reclamation projects might drive the dolphin, which is a first-class protected endangered species, into extinction.

On land, Hong Kong’s country parks face increasing pressure from developers. Although the total area of country parks has increased slightly from 413 sq km in 1997 to 443 sq km in 2020, our green landscapes are perpetually threatened by hill fires and heavy soil erosion caused by illegal and unsustainable activities such as motorcycle riding on mountain slopes and running or hiking beyond designated nature trails.

More alarming are the controversial proposals that would carve out parts of our country parks for housing development, while more feasible options, such as the use of brownfield sites, have not been seriously considered.

The city’s air quality has improved by certain metrics, such as the levels of respirable suspended particulates and sulphur dioxide. The roadside annual average concentration of nitrogen dioxide, however, stood at 70 micrograms per cubic metre in 2020, which is still a long way from the latest World Health Organization’s air quality guidelines of 10 micrograms per cubic metre.

This situation poses a long-term health threat to Hong Kong’s population. With roadside air pollution causing almost 3,000 premature deaths in 2021, the new administration must not underestimate this threat.

Lee has stressed that he will work to enhance the city’s overall competitiveness while pursuing sustainable development. The UN has set out 17 global Sustainable Development Goals to be achieved by 2030. Lee should begin working towards these goals immediately if he really wants to walk the talk.

Edwin Lau

Executive Director, The Green Earth

EN

EN Green Education Programme

Green Education Programme

Back

Back 06 Jul 2022

06 Jul 2022